|

VI.

PLANT COMMUNITIES

D. RIPARIAN COMMUNITIES

Once

water is in the ground after it rains, the soil acts

like a sponge, holding the water until it is either

taken up by plants or gradually pulled downward by

gravity into underground aquifers and springs or above-ground

seeps and creeks. Factors affecting the flow of a

stream are the rainfall, the timing of the rainy season,

the timing of primary plant growth and water usage,

watershed size, and bedrock geology. In Poly Canyon,

rainfall is typically between 20 and 30 inches, occurring

between October and April. Primary plant growth and

water usage is generally from April through September.

Larger watersheds tend to collect more rain, but smaller

ones, like Poly Canyon, are subject to more abrupt

changes brought on by natural episodic flooding, drought,

or fire or by anthropogenic activities such as overgrazing,

mountain biking, hiking, and pesticide runoff. If

a stream bed is solid bedrock, there is no chance

for water to penetrate, and all of it flows downstream.

On the other hand, water may penetrate the stream

bed to such a degree that it flows beneath the surface.

Brizzolara Creek experiences both of these scenarios.

The availability of moisture at the surface affects

the nature of the community, and it is the moist banks

and shores of fresh water streams, rivers, seeps,

springs, lakes, and estuarine marshes that give rise

to riparian communities. Riparius stems from ripa,

Latin for the "bank" or "shore of a stream or river."

Riparian

communities are dominated by one to several species

of anemophilous (wind-pollinated), winter-deciduous

trees with broad and/or soft-textured leaves. This

seems anomalous in the California setting given the

primarily evergreen nature of chaparral, coastal scrub,

and coastal live oak woodlands. "Deciduous islands

in an evergreen sea," our riparian forests are minor

refuges for riparian plants that flourished in a very

different climate during the Tertiary period millions

of years ago. While adjacent dry areas are stressed

by drought in summer, productivity does not suffer

in the riparian corridor where water and maximum sunlight

are available simultaneously. Riparian communities

are not restricted by climatic or edaphic conditions.

However, their size and species composition vary with

altitude, topography, the characteristics of their

banks, the amount of water carried by them, and the

proximity and size of adjacent underground water resources.

Physiognomically,

riparian forests are stratified, not unlike a tropical

jungle. Their canopies occur in layers formed by different

trees, shrubs, vines and lianas, and herbs. Found

in the uppermost canopy may be cottonwoods (Populus

spp.), sycamores (Platanus racemosa), and willows

(e.g., Salix laevigata.). In the intermediate

canopy are younger and/or other willows (e.g., Salix

lasiolepis). Western poison oak (Toxicodendron

diversilobum) often occurs in this community along

with blackberry (Rubus ursinus) as a tangled,

impenetrable mass of vines and shrubs. In the understory

are found such species as mugwort (Artemisia douglasiana),

monkeyflowers (Mimulus spp.), and creeping

snowberry (Symphoricarpos mollis).

The

deciduous nature of the dominant plant species affects

riparian communities in several ways. Seasonal fluctuations

occur in the light available to understory species.

Some herbaceous plants flower in winter when the trees

are dormant and bare, and more sunlight can reach

the understory. With the reduction in the direct sunlight

available in spring and summer, the temperature is

several to many degrees cooler than in adjacent areas

in full sun. This effect is enhanced by the presence

of flowing water, some of which evaporates, humidifying

and further cooling the environment.

In

drier areas, for example along intermittent creeks,

the riparian community may be quite reduced. Instead

of being forested, the area may be vegetated by an

assemblage of, for example, a few scattered sycamores

(Platanus racemosa) and expanses of treeless

zones with sun-tolerant plants such as rushes (Juncus

spp.) and sedges (Cyperus spp.). The vegetation

in the treeless areas may change seasonally, with

herbaceous riparian plants appearing in spring, then

dying back when their water supply dwindles. Localized

riparian areas may develop as a small community, a

monotypic population, or a lone tree, supported by

the water available at a spring or seep in an area

otherwise too dry.

As

mentioned, the seasonality of water availability under

the Mediterranean climate has a strong influence on

non-riparian communities such as chaparral and coastal

scrub. But riparian communities are also affected

by the seasonal flux in water availability. Streams

and creeks are dynamic, changing seasonally. They

may be flooded torrents in winter, their banks scoured,

denuded, and undercut. Then, in spring and early summer,

gentler waters prevail. In late summer and autumn,

creeks may host trickles, stagnant puddles, or completely

dried beds. The amount of water present varies from

year to year, and in many-year cycles. In years of

relatively low rainfall, certain plants may have the

opportunity to become established, only to be washed

away by the next flood.

Of

all the plant communities, the riparian occupies the

least amount of area in California. However, its varied

habitats support one of the most abundant and diverse

animal populations. Forty percent of the mammals and

reptiles, fifty percent of the birds, and more than

eighty percent of the amphibians in an area use the

riparian corridor for some or all of their needs.

Nearly thirty-five percent of our endangered species

depend on wetland habitats. Migrating birds use these

areas in spring and fall for shelter, food, and water;

insectivorous ones do so even in summer when insect

populations peak.

Riparian

vegetation provides food and shelter to organisms.

Organic matter or detritus (leaf litter, dead insects,

etc.) that falls into the stream also provides food

and shelter. Minerals are provided via runoff and

erosion of the stream bed and banks. Autotrophic organisms

thrive on this before becoming themselves a rich nutrient

base for aquatic insects and other invertebrates.

Living or dead, riparian vegetation forms the foundation

of the stream's food web. The shelter provided by

overhanging vegetation also moderates the temperature

of the water, enabling the growth and development

of aquatic invertebrates and the young fish who eat

them. Submerged vegetation and roots are habitat to

many organisms and also collect sediments that have

been eroded upstream. This helps keep the water clear

enough for fish and other aquatic species. It also

builds up the stream bank, creating new habitat for

terrestrial species. This ecological web is diagrammed

in Figure 14.

The

physical parameters whose variation most affects aquatic

organisms are stream depth, current velocity, substrate

composition, cover, water temperature, and pH. Disturbances

to riparian vegetation directly affect these characteristics.

Therefore, although fish and aquatic invertebrates

are considered to inhabit a strictly aquatic community,

their survival is, in no small part, dependent on

the good health of the adjoining riparian community.

The two environments, aquatic and terrestrial, are

inexorably linked.

Many

aquatic insects use terrestrial vegetation for food,

shelter, and reproduction. Insect orders in which

nearly all members have an aquatic stage (usually

the younger stages) include Ephemeroptera (mayflies),

Odonata (dragonflies), Plecoptera (stoneflies), and

Trichoptera (caddisflies). Other orders have at least

some families that are aquatic: Hemiptera (true bugs),

Neuroptera (alderflies, hellgramites, dobsonflies,

and fishflies), Lepidoptera (butterflies and moths),

Coleoptera (beetles), and Diptera (flies, craneflies,

and mosquitoes). See Table 11. Some species live on

partially immersed vegetation, others on decaying

grasses at the edge of the stream, others in seeps,

springs, or in ephemeral streams. The larvae of many

aquatic and semiaquatic Lepidoptera, Diptera, and

Coleoptera feed on vascular hydrophytes such as cattails

(Typha spp.) and bulrushes (Scirpus

spp.) Plecopteran adults live on streamside vegetation

and feed on epiphytic algae, young leaves, and buds.

Table

11

USE OF TERRESTRIAL VEGETATION BY AQUATIC INSECTS

|

ORDER

|

|

LIFESTAGE

|

|

| |

Egg

|

Nymph

|

Adult

|

|

Ephemeroptera

|

A1

|

A

|

T2

|

|

Odonata

|

A/t3

|

A

|

T

|

|

Plecoptera

|

A

|

A

|

T/a4

|

|

Hemiptera

|

A/T5

|

A/T6

|

A7/T

|

| |

Egg

|

Larva

|

Pupa

|

Adult

|

|

Neuroptera

|

T

|

A

|

T

|

T

|

|

Trichoptera

|

A/t

|

A/t

|

A/t

|

T

|

|

Lepidoptera

|

A/t

|

A/t

|

T/a

|

A/T

|

|

Coleoptera

|

A/t

|

A/t

|

T/a

|

A/T

|

|

Diptera

|

A/t

|

A

|

A/T

|

T

|

| A1: |

All

members are aquatic. |

| T2: |

All

members are terrestrial. |

| A/t3: |

Most

members are aquatic; some are terrestrial. |

| T/a4: |

Most

members are terrestrial; some are aquatic. |

| A/T5: |

Many

members are aquatic; many others are terrestrial. |

| A/T6: |

Insects

live on surface film, adjacent banks, and at aquatic

margins. |

| A7/T: |

Insects

may leave water to migrate. |

All

aquatic Neuroptera leave the water to pupate on land,

close to water: alderflies burrow in the soil along

the bank; dobsonflies and fishflies pupate in damp

soil or in decaying shoreline trees and stumps. Nearly

all aquatic Diptera pupate in moist streamside soil,

moss, or leaf litter. Mayfly eggs and numphs are aquatic,

then emerge as subimagoes (winged, but sexually immature

individuals) and perch on streamside vegetation for

minutes or days before molting to the imago (adult)

stage. Many aquatic insects oviposit on vegetation

in or above water. When the nymphs hatch, they wriggle

or fall into the water where they find food and shelter.

Many aquatic insects are omnivorous, their food requirements

changing with their instars (sexually immature developmental

stages).

California

has about 120 native amphibians and reptiles, many

of which are important ecological elements in the

riparian community. All amphibians (except lungless

salamanders, Plethodontidae) require aquatic environments

to complete their life cycles. Many herpetofaunal

species utilize the riparian zone thoughout their

lives: frogs (Rana spp.), salamanders (some

Batrachoseps spp.), turtles (Clemmys spp.),

and most garter snakes (Thamnophis spp.). Others

use it primarily for breeding: salamanders and newts

(Ambystoma spp. and Taricha spp.) and

some toads (Bufo spp.). Salamanders (Ensatina

spp.) and lizards (Gerrhonotus spp.), that

have fairly generalized habits in mesic environments

(further north), are closely associated with the riparian

community in more xeric environments such as Poly

Canyon. Whiptails (Cnemidophorous spp.), gopher

snakes (Pituophis spp. ), and kingsnakes (Lampropeltis

spp.) have fairly generalized habitat requirements,

but frequent riparian communities and their ecotones.

Some use the riparian system as a corridor for dispersal

and as islands of habitat in areas where the otherwise

arid ecological conditions would not permit. Among

these is the ringneck snake (Diadophis punctatus).

See Tables 12 and 13.

In

Poly Canyon, a single, uniform riparian community

does not line the creek. Rather the vegetation varies

along its course and in the moist areas of the adjacent

hillsides both in the cover and species composition.

The headwaters of Brizzolara Creek consist of varied

springs, seeps, and intermittent rivulets and trickles

occurring from the ridge above the railroad tracks

to the steeper hillsides above Peterson Ranch. Some

of these are deep draws treed with coast live oak

(Quercus agrifolia). Some are exposed rocky

places vegetated by a few sycamores (Platanus racemosa),

bay-laurel (Umbellularia californica), and

shrubby and herbaceous associates such as hummingbird

sage (Salvia spathacea), western poison oak

(Toxicodendron diversilobum), and bedstraw

(Galium spp.). In some areas, water surfaces

in a grassy depression between steep slopes where

one finds sedges (Carex spp.), rushes (Juncus

effusus, J. patens, and J. phaeocephalus),

watercress (Rorippa nasturtium-aquaticum),

seep monkeyflower (Mimulus guttatus), fleabane

daisy (Erigeron philadelphicus), curly dock

(Rumex crispus), and willows (Salix

spp.). In many places water flows seasonally, but

creates no obvious changes in the chaparral, coastal

scrub, or grassland vegetation growing there.

At

lower elevations (from the base of the grade below

the tracks and down the valley floor to the area adjacent

to the Botanic Garden), the creek appears more consolidated.

Its banks are intermittently vegetated by sycamores

(Platanus racemosa), coast live oaks (Quercus

agrifolia), and understory associates - the ubiquitous

western poison oak (Toxicodendron diversilobum),

some coffeeberry (Rhamnus californica), blackberry

(Rubus ursinus), and herbaceous forbs and grasses.

Cattle fences cross the creek in several spots, as

does the dirt road. Cattle feed, drink, and laze about

in the creek at several points.

Table

12.

USE OF RIPARIAN SYSTEMS BY AMPHIBIANS

TYPE

OF USE

|

Constant

|

Breeding

|

General

|

|

Red-legged

frog

Rana aurora

|

California

newt

Taricha torosa

|

Ensatina

Ensatina eschscholtzi

|

|

Foothill

yellow-legged frog

Rana boylii

|

Western

toad

Bufo boreas

|

Pacific

slender salamander

Batrachoseps pacificus

|

|

|

Pacific

treefrog

Hyla (Pseudacris) regilla

|

Arboreal

salamander

Aneides lugubris

|

Table

13.

USE OF RIPARIAN SYSTEMS BY REPTILES

TYPE

OF USE

|

Constant

|

Arid

|

General

|

|

Western

pond turtle

Clemmys marmorata

|

Western

skink

Eumeces skiltonianus

|

Western

fence lizard

Sceloporus occidentalis

|

|

Common

garter snake

Thamnophis sirtalis

|

Ringneck

snake

Diadophis punctatus

|

Western

whiptail

Cnemidophorus tigris

|

|

|

Western

terrestrial garter snake

Thamnophis (Nerodia) elegans

|

Southern

alligator lizard

Gerrhonotus multicarinatus

|

|

|

|

California

legless lizard

Anniella pulchra

|

|

|

|

Racer

Coluber constrictor

|

|

|

|

Striped

racer

Masticophis lateralis

|

|

|

|

Gopher

snake

Pituophis melanoleucus

|

|

|

|

Common

kingsnake

Lampropeltis getulus

|

|

|

|

Western

rattlesnake

Crotalus viridis

|

Near

the Botanic Garden, the creek bed and banks are bedrock.

The banks rise steeply from the creek and the vegetation

forms a riparian forest over the water with dominant

elements such as coast live oak (Quercus agrifolia),

bay-laurel (Umbellularia californica), western

poison oak (Toxicodendron diversilobum), and

a coast redwood (Sequoia semprevirens) that

was planted west of the road bridge. The understory

includes creeping snowberry (Symphoricarpos mollis),

mugwort (Artemisia douglasiana), horsetails

(Equisetum spp.), seep monkeyflower (Mimulus

guttatus), coffee fern (Pellaea andromedifolia),

goldback fern (Pentagramma triangularis), California

polypody (Polypodium californicum), hedge-nettle

(Stachys bullata), and miner's lettuce (Claytonia

perfoliata). Wildflowers common along the trail

just west of the creek include blue-eyed grass (Sisyrinchium

bellum), blue dicks (Dichelostemma capitatum),

Chinese houses (Collinsia heterophylla), California

poppies (Eschscholzia californica), Phacelia

(Phacelia distans), and Dudleya (Dudleya

lanceolata).

As

the creek reaches the lower elevations within the

narrow part of Poly Canyon, the bed material consists

of more eroded sands, gravels, and occasional boulders.

The water disappears intermittently below the surface,

particularly in the warmer months. Sycamores (Platanus

racemosa) and willows (Salix spp.), bay-laurels

(Umbellularia californica), an occasional eucaplyptus

(Eucalyptus globulus, introduced), and coast

live oaks (Quercus agrifolia) take turns in

dominance. There are numerous areas with little tree

cover where ruderal communities and grasslands reach

the creek. The creek is crossed in several spots by

barbed wire and old wooden fencing. Cattle use the

creek bed. Where the road's retaining wall has broken,

the cement slab remains partly in the creek and on

its bank. There has been effluent and runoff reported

from the feed lot and seepage from the dump. Several

sites along the road are noted to be undercut and

in danger of collapse into the creek. Several springs

are reported in the dump.

- Plants

which dominate riparian areas in Poly Canyon include:

- Blue

gum (Eucalyptus globulus, Myrtaceae)

-

Western sycamore (Platanus racemosa, Platanaceae)

-

Black cottonwood (Populus balsamifera ssp.

trichocarpa, Salicaceae)

-

*Coast live oak, encina (Quercus agrifolia,

Fagaceae)

-

Arroyo willow (Salix lasiolepis, Salicaceae)

-

*California bay, California laurel, pepperwood,

bay-laurel (Umbellularia californica, Lauraceae)

-

-

- Associate

species include:

-

*Mugwort (Artemisia douglasiana, Asteraceae)

-

*Chaparral broom, coyote bush, coyote brush (Baccharis

pilularis, Asteraceae)

-

Sedges (Carex senta and C. spissa,

Cyperaceae)

-

-

Umbrella sedge, nutsedge, galingale (Cyperus

eragrostis, Cyperaceae)

-

Spikerush (Eleocharis macrostachya, Cyperaceae)

-

Giant horsetail (Equisetum telmateia, Equisetaceae)

-

Rush (Juncus effusus, Juncaceae)

-

Spreading rush (Juncus patens, Juncaceae)

-

Brown-headed rush (Juncus phaeocephalus,

Juncaceae)

-

Seep or common monkeyflower (Mimulus guttatus,

Scrophulariaceae)

-

Water cress (Rorippa nasturtium-aquaticum,

Brassicaceae)

-

Ground rose (Rosa spithamea, Rosaceae)

-

*California blackberry (Rubus ursinus, Rosaceae)

-

Curly dock (Rumex crispus, Polygonaceae)

-

*Blue elderberry (Sambucus mexicana, Caprifoliaceae)

-

Small-headed bulrush (Scirpus microcarpus,

Cyperaceae)

-

*Western poison oak (Toxicodendron diversilobum,

Anacardiaceae)

-

Broad-leaved cattail (Typha latifolia, Typhaceae)

Descriptions

of plants dominant in Poly Canyon's riparian communities

follow.

|

Charles Webber

*Blue

gum (Eucalyptus globulus, Myrtaceae)

This evergreen tree grows to about 45 m. (150

feet) tall. Its bark peels off in irregular

patches seasonally. The glaucous green leaves

of the older branches are 10- to 20 cm. (4 to

8 inches) long, lanceolate, somewhat sickle-shaped.

They are very aromatic. The sepals and petals

are fused into a warty-textured bud cap from

which a profusion of cream-colored stamens emerges.

Bloom is from December through May. The 2-cm.

(1-inch) fruit is a warty, woody capsule. Blue

gum is found in disturbed areas.

Eucalyptus

comes from the Greek and means "well covered,"

referring to the bud cap. Globulus means

"small ball" or "small sphere." This species

is native to Australia. The Californian environment

is similar to that of its native Australia,

and it was brought here to be farmed for wood

for the furniture industry. However, it turned

out not to be suitable for that. It has proven

to be extremely invasive. Here there are no

animals that eat blue gum and keep its growth

in check, and it is very prolific. Also, because

of the oils it exudes, most other plants cannot

grow in its immediate vicinity. One might consider

a blue gum woodland as a blue gum barrens.

|

|

Western

sycamore (Platanus racemosa, Platanaceae)

This is a 10- to 35-m. (30- to 115-foot) deciduous

tree. Its bark peels off giving its trunk and

main branches a puzzle-like appearance. The

tree looks gnarled and it grows at seemingly

odd angles. This is due to anthracnose (Gnomonia

platani), a fungal infection. In years of cool,

wet spring weather, trees can be completely

defoliated by the disease. A new crop of leaves

later forms in the drier summer months. The

tree has 13- to 33-cm. (5- to 13-inch) palmate,

five-lobed, tomentose leaves. It has 1-cm. (1/2")

heads of yellow-green male flowers and red female

flowers from February through August. The bloom

is followed by a 2- to 3-cm. (1-inch), dense,

globose head of achenes. Western sycamore is

found in canyon and streamside habitats.

Platanus

comes from the Greek platys "broad,"

referring to the size of the leaves. Racemosa

comes from the Latin racem "a cluster,"

referring to the chains of fruiting heads.

Early

Californians fashioned the burl-like growths

of the aliso into bowls.

|

|

Brother Alfred Brousseau

Black

cottonwood (Populus balsamifera ssp.

trichocarpa, Salicaceae) This dioecious,

deciduous tree reaches 30 m. (100 feet) tall.

It has grayish, furrowed bark. Its 3- to 7-cm.

(11/4-to 23/4-inch) finely toothed, ovate leaves

are dark green above and paler green beneath.

Its inconspicuous flowers bloom in 3- to 8-cm.

(11/4- to 31/4-inch) catkins from February through

April. The 3- to 12-mm. (1/8- to 1/2-inch) fruit

is a dry capsule with hairy seeds. Black cottonwoods

are found at streamside places.

The

name Populus may be derived from pal

"to shake," referring to the way leaves of some

species, such as the quaking aspen, quiver in

a breeze. Balsamifera refers to the fragrant

gum covering the buds of this tree. Trichocarpa

means "hairy fruit."

The

alamo was used in a number of ways by

native Californians: housing, culinary implements

and containers, and clothing. Its bark made

a tea used to bathe broken or bruised limbs.

The leaves and bark were made into a poultice

to treat bruises and cuts. In Chumash oral tradition,

Old Man Sun carries a torch made of the inner

bark of cottonwood.

|

|

*Coast live oak, encina (Quercus agrifolia,

Fagaceae)

click

here for description

|

|

Arroyo

willow (Salix lasiolepis, Salicaceae)

This deciduous dioecious willow can grow to

be a 10-m. (30-foot) shrub or tree. It spreads

underground to form extensive clonal groups.

It has 4- to 12-cm. (11/2- to 5-inch) long,

narrow leaves on yellowish twigs. Its inconspicuous

flowers bloom in 15- to 70-mm. (1/2- to 23/4-inch)

catkins from March through May. Arroyo willows

are common in meadows and at springs.

Salix

is the classical Celtic name for the willow:

sal means "near," lis means "water."

Lasio means "shaggy/hairy," lepis

means "scale."

The

Spanish name for willow is sauce. The

leafy branches of willows were spread out for

a feverish person to lie on. A decoction of

its bark and leaves was used to bathe hemorrhoids.

The tea was also used to treat sore throats

(as a gargle) and to cure fevers and malaria.

Today, salicylic acid (from Salix) is

the active ingredient in aspirin. Chumash chewed

the bark to strengthen their teeth. They used

branches as fishing poles, switches, whips,

and firewood.

|

*California bay, California laurel, pepperwood,

bay-laurel (Umbellularia californica,

Lauraceae)

click here

for description

|

Associate

species include:

|

*Mugwort (Artemisia douglasiana,

Asteraceae)

click here for

description

|

|

|

*Chaparral

broom, coyote bush, coyote brush (Baccharis

pilularis, Asteraceae)

click here

for description

|

|

|

image

unavailable

Sedge

(Carex senta, Cyperaceae) This sedge

has up to 1-m. (40-inch) stems that are solid

and usually triangular. It grows in large, dense,

raised clumps connected by rhizomes. Leaf blades

are 3 to 5 mm. (1/8 to 1/6 inch) wide. Spikelets

measure approximately 21/2 to 5 cm. (1 to 2

inches). They have male flowers toward the tip

and 25 to 100 sessile perigynia below. Perigynia

are sac-like structures that house the female

flowers. Female flowers have two stigmas each.

The 3- to 4-mm. (1/8- to 1/6-inch) fruit is

a two-sided achene. This sedge is found along

streambanks, among rocks in stream channels,

and among rocks in stream channels.

Carex

comes from the Latin and means "cutter," in

reference to the sharp edges of the leaf and

stem. Senta is Latin for "rough, foul,

uncared-for."

|

|

|

Charles Webber

Sedge

(Carex spissa, Cyperaceae) This sedge

has 1- to 2-m. (3- to 61/2-foot) stems that

are solid and usually sharply triangular. It

grows in large, dense clumps connected by rhizomes.

The inflorescence is at least 4 cm. (11/2 inch)

long. The top one to five spikelets are male,

and there are at least two female spikelets

below, each with 150 to 300 perigynia. Perigynia

are sac-like structures that house the female

flowers. Each female flower has three stigmas.

The fruit is a three-sided, beaked achene. This

sedge occurs along waterways and hillside seeps.

It may occur in serpentinitic areas.

Carex

comes from the Latin and means "cutter," in

reference to the sharp edges of the leaf and

stem. Spissa means "compact, thickened."

|

|

|

Charles Webber

Umbrella

sedge, nutsedge, galingale (Cyperus eragrostis,

Cyperaceae) Umbrella sedge is a perennial with

10- to 90-cm. (4- to 36-inch) stems. The stems

are solid and triangular. The terminal inflorescence

contains 20 to 70 flat spikelets. Flowers are

bisexual with three stigmas. The fruit is a

tiny brown, three-sided, beaked achene. Umbrella

sedge is found along streambanks and in ditches.

Cyperus

is the ancient Greek name for "rush" or "sedge."

Er means "spring" and agrostis

means "grass."

|

|

|

Spikerush

(Eleocharis macrostachya, Cyperaceae)

This is a 1/2- to 1-m. (11/2- to 3-foot) perennial

that spreads by rhizomes. Stems are round and

solid. The inflorescence is a single, terminal

spikelet of bisexual flowers with two-branched

styles. The fruit is a two-sided or round whitish-brown

achene. Spikerush is found in marshy areas,

along pond margins, and in ditches.

Eleocharis

is Greek for "marsh grace." Macro is

Latin for "large," stachus is Greek for

"point."

|

|

|

Giant

horsetail (Equisetum telmateia, Equisetaceae)

This ia a perennial that spreads via rhizomes.

Its stems are hollow (except at the nodes).

They are ridged lengthwise. Sterile green stems

are 30 to 100 cm. (1 to 3 feet) tall and have

many slender, whorled branches. The sterile

stems form in late winter and persist through

the growing season. Fertile, fleshy, brown,

unbranched stems are 15 to 45 cm. (6 to18 inches)

tall and are tipped by cone-like strobili that

produce masses of green spores. The fertile

stems are ephemeral, produced in winter and

withering soon afterward. Giant horsetails are

found along streambanks, in ditches, and in

seepage areas.

Equus

is Latin for "horse," seta means "bristle,"

and telma means "pond."

Canutillo

and caņutillo are Spanish words derived

from the Mozarabic cannut. They are the

diminutive forms of canuto and caņuto,

meaning small tube or container or, botanically,

internode. Horsetails were used by Chumash as

sandpaper, for gray dye, as a purgative, and

as a cure for venereal disease.

|

|

|

Rush

(Juncus effusus, Juncaceae) This is a

perennial species. Its 6- to 130-cm. (21/2-

to 51-inch), round stems grow in clumps and

spread by stout, branched rhizomes. Leaves are

basal and have no blade. The terminal inflorescence

appears to be lateral; each has many flowers.

Each flower has three stamens. The fruit is

a somewhat truncate obovoid capsule with 1/2-cm.

(1/4-inch) seeds that have a single minute appendage.

This rush is found in wet places.

Juncus

comes from the Latin, "to join" or "to bind."

Effusus means "spread out, extensive,

loose, unrestrained."

Juncos,

in Spanish, were used extensively by Chumash

in basketry and other weaving projects (clothing,

beading, mats). They were also used to string

up abalone to dry.

|

|

|

Spreading

Rush (Juncus patens, Juncaceae) This

is a perennial species. The 30- to 90-cm. (12-

to 36-inch) stems form clumps and spread by

stout branched rhizomes. The bluish-gray-green

stems are distinctively grooved lengthwise.

The leaves are basal and bear no blades. The

terminal inflorescence appears to be lateral.

Each has many flowers, these with six stamens

each. The fruit is a spheric capsule with a

soft beak. Seeds are 1/2 cm. (1/4 inch) long.

They are asymmetric and bear minute appendages.

Spreading rush occurs in marshy places.

Juncus

comes from the Latin, "to join" or "to bind."

Patens means "spreading" or "open."

Juncos,

in Spanish, were used extensively by Chumash

in basketry and other weaving projects (clothing,

beading, mats). They were also used to string

up abalone to dry.

|

|

|

Brown-headed

rush (Juncus phaeocephalus, Juncaceae)

This is a perennial species. It has 10- to 50-cm.

(4- to 20-inch) stems spreading from stout rhizomes.

The stems and leaf blades are flat. The inflorescence

has a one to many flower clusters. Each flower

has six stamens and stigmas that are long-exserted.

The fruit, a capsule, has a long, tapered beak.

The ovoid seeds are 1/2 cm. (1/4 inch) long.

This rush is found in moist places.

Juncus

comes from the Latin, "to join" or "to bind."

Phaeo means "brown" or "dark," cephalus

means "head."

Juncos,

in Spanish, were used extensively by Chumash

in basketry and other weaving projects (clothing,

beading, mats). They were also used to string

up abalone to dry.

|

|

|

Seep

or common monkeyflower (Mimulus guttatus,

Scrophulariaceae) The seep monkeyflower is usually

a perennial. It is 5 to 100 cm. (2 to 40 inches)

tall. It spreads by stolons. It is herbaceous

and has fleshy, green, opposite, toothed, rounded-ovate

leaves. It has bright yellow flowers with red

spots in their hairy throats. They bloom from

March through September. The fruit is an oval

capsule. Seep monkeyflower is found along streambanks

and wet places.

Mimulus

comes from the Latin mimus "a comic actor"

because of the "monkey-face" markings on the

flowers of some species of Mimulus. Gutta

means "drop," referring to the red droplet-like

markings on flowers in this species.

|

|

|

Brother Alfred Brousseau

Water

cress (Rorippa nasturtium-aquaticum,

Brassicaceae) This perennial herb is often prostrate

in standing water or slow-running streams. The

stems root at the nodes. Its shiny green leaves

are pinnately divided with leaflets measuring

to 10 cm. (4 inches) long. The 3-mm. (1/8-inch)

flowers have four white petals each and bloom

from March through November. The long, slender

pod-like fruits are called siliques. Water cress

is found along streams and at springs.

Rorippen

is an old Saxon word. Nasturtium means

"twisted nose" because of the pungency of the

plants. Aquaticum means "found in the

water."

,

in Spanish, were introduced from Europe and

reportBerrosed from Price Canyon as early

as 1769. They were eaten raw (for liver ailments)

and cooked (as tea for hangovers).

|

|

|

Brother Alfred Brousseau

Ground

rose (Rosa spithamea, Rosaceae) This

is a 50-cm. (20-inch) dwarf shrub with rhizomes

and prickly stems. It has two to four double-toothed

leaflets per leaf. Each inflorescence has one

to ten pale pink flowers. Fruits are achenes

enclosed in the hip. Ground rose is found in

open woodlands, as well as chaparral, especially

after fire.

The

etymology of rosa is unknown. It may

be either the ancient Latin name for rose or

derived from the Celtic rhod meaning

"red." Spithamea derives from spithama

meaning "a span, measure equal to the distance

between the first and last fingers of an outstretched

hand, approximately seven inches."

The

fruit of rosa de Castilla, in Spanish,

was used by Chumash. It was eaten raw or strung

for necklaces or earrings. The petals were dried

and used as a tea to cure colic, as an eyewash,

to soothe teething babies, and, powdered, as

talc.

|

|

|

*California blackberry (Rubus ursinus,

Rosaceae)

click

here for description

|

|

|

Curly

dock (Rumex crispus, Polygonaceae)

This is a 30-cm to 120-cm. (1- to 4-foot) introduced

perennial species. It has a taproot. Its 50-cm.

(20-inch) lanceolate leaves have curled margins.

Dense, leafy panicles of green flowers bloom

most of the year; then shiny brown fruits, achenes,

develop. Curly dock occurs in disturbed places.

Rumex

is Latin for "sorrel." Crispus means

"curled."

Lengua

de buey ("bull's tongue" in Spanish) was

brought from Eurasia, but it is suspected that

the native Rumex salicifolius was used

by Chumash in the same manner. Its leaves were

eaten as greens; the peeled, raw stem resembles

a sour version of celery; the seeds were pounded

into a mush; and the root was boiled into a

tea to cure stomach ailments.

|

|

|

*Blue elderberry (Sambucus mexicana,

Caprifoliaceae)

click here

for description

|

|

|

Charles Webber

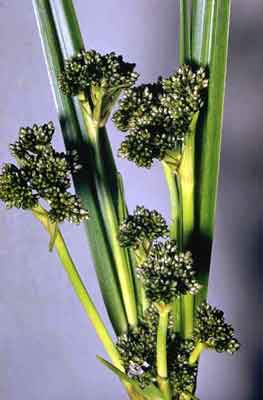

Small-headed

bulrush (Scirpus microcarpus, Cyperaceae)

This is a 30- to 150-cm. to (1- to 5-foot) perennial

with hollow triangular stems. Its inflorescence

is panicle-like and consists of fifty or more

spikelets in head-like clusters of four to twelve

at branch tips. This bulrush occurs along streambanks,

in wet meadows and marshy areas.

Scirpus

is the classical name for "bulrush." Microcarpus

means "tiny fruit."

|

|

|

*Western poison oak (Toxicodendron diversilobum,

Anacardiaceae)

click here

for description

|

|

|

Broad-leaved

cattail (Typha latifolia, Typhaceae)

This is a perennial that spreads by rhizomes.

It grows in water (not underwater) or in drier

soil. It has a spike-like, terminal, cylindrical

inflorescence of a thousand or more flowers.

The male flowers grow toward the tip of the

inflorescence; the female flowers below. Flowers

bloom from June to July. This cattail is common

in marshy areas and ponds.

Typha

is the ancient Greek name for "cattail." Latifolia

means "broad leaf."

Tule

ancho means broad, wide tule, in Spanish.

Tules were used by Chumash for thatching, weaving

mats and canoes, and occasionally in basketry,

and for splinting broken limbs. The ashes were

used to massage the skin for relief from rheumatism.

Stems were made into "straws" used for sucking

liquid tobacco. Tule was used for archery

targets and in rituals. Two other types of tules

were recognized by the Chumash: tule redondo

(round, the shape of the stems): Scirpus

acutus and S. californicus; and tule

esquineado (probably an aberration of esquinado

meaning having corners, referring to the triangular

stems): Scirpus americanus.

|

|

|